Biography

Olivier Zappelli, « OZ », born in Lausanne, Switzerland, on April 1966. In 1990, after hissudies at Fine Art Schcool, he starts a traveller’s life. His first destination is Haïti. There hediscovers voodoo religion as well as the naive and fantastic art of the magic island. Afterthat, he stays in India, where he becomes a sadhu, a shivaistic monk. For several years, hepaints mythological murals in temples throughout north India.

In 1994, during a stay in Norway, he reconnects with oil painting, sinked into oblivion sincethe Fine Art School. In 1996, his art is celebrated by the International Center of Fantastic Art at the Gruyères Castle, Switzerland. There he holds his first solo exhibition. Since 1999, Oz also takes part in group exhibitions in Switzerland, Italy, Spain, France, Germany, Austria, Holland, Denmark and USA.

“OLIVIER ZAPPELLI, HIPPIES, GODDESSES AND GODS”

By Etienne Chatton, Founder of the International Center of Imaginary Realism, Château de Gruyère, Switzerland

Olivier Zappelli was born in Lausanne on 2 April 1966 at 00:20 am. Aries, ascendant Sagittarius: fire of fire, with the bonus of a fire horse in the Chinese zodiac. A player of extremes, destabilised by any balance, he reveals himself from childhood curious about everything, consumed by desires. On him, the offspring sees converging a picture of ascendants where political passion in the male lineage mixes with a taste for the arts in the female lineage. From an old Piedmontese family, grandfather Zappelli, the socialist deputy mayor of Intra-Verbania, sat in the Roman Senate; after the rise of fascism and the coming to power of Mussolini forced him into exile in Switzerland. On his mother’s side, the Lombards of Neuchâtel are of Cévennes descent. The Desert Museum has honoured the descendants of these exiled Protestants. The neo-classical paintings of great-aunt Jeanne Lombard will be on display alongside those of grandfather Théodore Delachaux and the engravings of great-uncle Aimé Montandon.

In high school, Latin section, the idiom of the ancestors puts the schoolboy in lethargy. A protean dunce, he only wants to scribble while the disciplinary board inflicts the worst violence on him. At the age of sixteen, he was nevertheless entrusted with a comic strip commemorating the 400th anniversary of Collège St-Michel. The work, which is forbidden to be entitled The antics of St Canisius, puts him on probation for a while. His execrable grades, however, forced him to leave the venerable institution two years before the baccalaureate. Exasperated, his father enrolled him at the Beaux-Arts of Sion, where the dazzling illumination of Minimal Art is given in permanent happening, but the beatnik, opting for tag rather than wall tachism, refuses to devote himself to it body and soul.

Olivier Zappelli then enrolled at the Maximilien de Meuron school in Neuchâtel. A hippie in a fur coat and tree mop, he sucks in the joint with the air of the times. By militating for Che Guévara in the ecstasy of piercing, he acquires notions of comparative anatomy as the spirit comes to girls. By copying the friezes of the Parthenon, he still swallows the rudiments of aesthetics and the history of art. But in his third year, he decides to boycott the modelling class; a fanatic of constructivism, the master only dreams of spheres and cubes while Olivier only wants to paint. One stormy day, the dean, showing his authority, throws all his production on the street. An exchange of blows! Expulsion! Back in Fribourg, the future genius decides to punish the impudent despot. He concocts a recipe for dung alcohol which he will serve cold in the time of revenge. Self-taught in the techniques of painting, modelling and tutti quanti, and with his knowledge of elementary chemistry, Olivier decides to play Zap II the return. Having come to pay his respects to the violent headmaster, he sprinkles the hall of honour of the school with liquid nausea, the smell of which will linger for a long time.

In a chaotic search for himself, Brother Olivier enters the Cistercian monastery of Hauterive. The Abbot, eager to test the obedience of the postulant, asks him to give up painting. Two months to macerate out of the shimmering waters of creation before the artist decides to cross the fence. A mystical interlude that a detective would classify as a hit-and-run.

Only tolerated by the official authorities, who sponsor the international competition, non-art leaves many holes in the cheese of the state percentage. Early on in their careers, the elders are into performance. Will Olivier be satisfied with the vaguely anarchist remarks uttered by the revolutionaries in slippers, who advocate an art of destruction? As the son of a bourgeois, who has been feeding on the ears of a judge father and a press correspondent grandfather renowned for his geopolitical chronicles, a Zappelli cannot confine himself to programming the void. If Art is questioned from the order of the world, it is first of all from a world of ideas.

For the man who laughs, horror always has a derisory side. Humour allows one to bear the tragic. The comic strip is the ideal medium for those who are looking for a figurative way out of the usual clichés. The bubbles of the comic strip are manifestos waiting for myths. Richard Corben inspires the younger generation with his irritating heroes. Just like the Rolling Stones, his art combines vulgarity, hatred and sadism in a pleasantly tonic poetics. For Zappelli, the revolution will be hilarious.

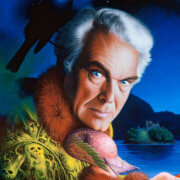

Olivier Zappelli’s compositions strike them with the acronym OZ. Dare. A programme: daring to take risks, making it a constant challenge. Oriental idealism has rushed into the breach opened by the pornographic industry; would it go so far as to draw dirty tricks, images of administrative pipes and the introduction of gadgets with dubious hygiene? If he has committed this sin — nothing human is foreign to him — let the critics see in these sins of youth an encouragement to humility.

In the meantime, Olivier Zappelli has joined the post office administration. He stamps letters and lugs parcels. By the time he collects a few dollars, the cicada reopens its wings and flies to Haiti. Animism is the original form of all belief. On All Saints’ Day, the whole island is transformed into a gigantic seance of spiritualism. As a neophyte, OZ takes part in countless voodoo ceremonies. Too intellectual or not enough abandonment, he will never reach the trance of the innocent souls and bodies over which the spirits ride. Besides, this teeming life lacks asceticism. By chance, a book on India brings him enlightenment. Via the airport of Port-au-Prince. Immediate boarding.

From New Delhi, armed with rustic virtues, the adventurer sets off on the roads of India. Hardened by pleasure more than by effort, he tastes the intoxication of solitude and the joy of living to the fullest. In pursuit of his own secrets, he immerses himself in the Ramayana. The hunger for superficial mirages is appeased, the dull boredom of everyday life returns. Although the sweet prattle, woven in garlands around faith, leaves him sceptical, he decides to try the experience of monastic life. In order to conquer a highly tantric mastery, the complete rebel, kicked out of school and the army, submits to all the rules.

Bare-chested and barefoot, the salmon dhoti, the glorious emblem of the itinerant monk, covers the least glorious part of his anatomy. With his beard and hair covered with ashes of cow dung, he begs for his food in the Hindi language. Still addicted to the need to paint, at the temple of Kajuraho, Hanuman Mandir, he receives a mandate to represent the monkey god Hanuman. Complete happiness: a six-metre long fresco that he completed before reaching Bhairotik, Kal Bhairo Mandir, where the monks ordered him to illustrate an episode of the Mahabharata. The amazed villagers come to bow before the sacred images and touch the feet of the venerable sadhou.

From the outset, OZ confines itself to symmetrical compositions. As in oriental music, this classical scheme will serve as the harmonic fundamental; it is the continuous base supporting the melodic discourse, where the sithar embroiders its variations ad infinitum. Often, his painting conceals a duality that takes him from the dark to the light. This vertical stretching is in accordance with the principle of liberation. From saturation to clarity, the spirit is released from its gangue of matter. His technique, which saturates the colour, joins the motto of the expressionist rapins: oil on canvas is oil on fire. The tones, which he superimposes on his canvas in very thin layers, let a vibrant light penetrate under his glazes.

Neither really childish nor really adult, he has kept a torn soul: the innocent Peter Pan in perpetual struggle against the ferocious Dracula. This fawn-like appetite for the brutal efficiency of the poster requires these contrasts between harmony and delirium. The subjects arise spontaneously. He keeps in reserve multiple themes that he neither seeks to analyse nor to censor. He brings them out when a visceral desire imposes their projection. This urgency of the unconstructed idea can only be explained at the end of the journey, when innumerable embellishments have enriched it.

In his canvases, which he exploits in parallel, he manages to interweave contemporary references, mixed with the most rigorous classicism. Opposing the light and the dark, the immense and the derisory, he makes a tiny cartoon cohabit with a giant in the Sistine Chapel. The diversity of these contributions creates tension; they generate intensity. Contestation becomes a source of poetry. Summoned to explain himself, OZ justifies his fascination with the great classics: “Michelangelo for the power he gives off from his bodies, for his bright orange drapes and apple green shadows. Dürer who breaks all taboos. He dared, so I can”.

The little gods who yelp in the darkness demand less convention than truth. By serving dubious masses, OZ only had to mimeograph his mythological borrowings. Foolish with good feelings, Oz could pour out his heart to the point of implosion in his children’s portraits. Taken hostage by good society, he would have honoured the priestesses of the temple. As proselytes, they would have been able to inspire the anarchist with their moralizing vision of the class struggle. So many wretched people have fallen there, who no longer even have the excuse to suffer the pressure of the reactionaries. Left to delirium alone, he remains conscious of the limits of the bullshit that it is good manners to overstep.

The portrait of a woman is like a marriage proposal. Alas, the monks refrain from such requests and if they have the desire to paint, they only honour the Blessed Virgin. OZ completed his novitiate in a monastery of Hindu mystics practising tolerance and love of mankind. The sacred principles of this vocation in pursuit of the divine were to bring him to the summit of liberation. But he renounced all his vows, including the vows of chastity. If he was able to keep his virile attributes, he came out marked by the experience of chastity. Would fatality have caused him to fall back into misogyny, which has always been the rut of Christian monasticism?

The Clinton years dealt the final blow to intolerance. But sexual freedom was tinged with iconoclasm. Not all macho men and women are Muslims. They feign respect, but it is to better practice systematic gutting. Whether literary or plastic, their criticism stigmatises the intrigues and ambitions of the muses of power as much as their shamelessness. In this Mecca of political correctness that the world of women has remained, a puddled has-been thinks she has the right to demand that a painter make the apotheosis of the sinuous blonde? Lucidity often makes men cowardly; macho for fear of appearing complacent, OZ was never cowardly. Thanks to his sponsors for never forcing him to spread sweets on the verge of a diabetes crisis.